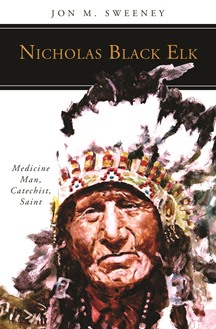

Nicholas Black Elk

Medicine Man, Catechist, Saint

Jon M. Sweeney

Liturgical Press, 2020

Reviewed by Jeanne Torrence Finley

Originally published in Englewood Review of Books and used by permission

From the beginning of Nicholas Black Elk, Jon Sweeney makes it clear that his subject has been misunderstood because of the complicated life he lived as both an Oglala Lakota wicasa wakan, or “holy man,” and Catholic catechist. Sweeney attributes part of the misunderstanding to another book, published in 1932, Black Elk Speaks: Being the Life Story of a Holy Man of the Oglala Sioux as told through John G. Neihardt. Two years earlier Neihardt, the poet laureate of Nebraska and an amateur anthropologist, had gone to Pine Ridge reservation in 1930 because he wanted to find someone to be the hero of an exotic tale of a Native American who was “a living icon of the tears and epic struggle of the native peoples of the Americas” (xii). Black Elk Speaks became the most popular book ever published about a Native American, and especially so in the 1960s and 1970s, a time of great spiritual search and fascination with non-Christian religious traditions. It has formed the mistaken notion that Black Elk’s faith was strictly and only Native American until he died.

In Nicholas Black Elk, Sweeney tells the other half of the story– the one that Neihardt intentionally did not tell–of Black Elk’s life as a Catholic catechist. As Sweeney explains, “”Black Elk’s passionate involvement in historic Catholicism would have dampened the message of any mythic portrayal of a saddened, aging Lakota who had seen his people humiliated, the Plains decimated, and a pristine nomadic way of life gone forever. A Native man teaching the Gospel in a church was not the picture a mythmaker wanted to paint” (xvi).

Born in Lakota territory in 1866, Black Elk was the son and grandson of medicine men, and as such, they had powers of healing for their people. As expected in a child who would also become a medicine man, Black Elk had a number of mystical experiences. The most formative was his “Great Vision” in which he was taken into the clouds to see his grandfathers from all over the world, who gave him gifts and told him that he would have great powers to heal as well as the vocation to lead his people down the red road toward the sacred hoop to become a great nation. Nevertheless, they would also have great troubles. As the vision continued Black Elk went with his sixth grandfather to the world’s highest mountains where they could see those troubles, but there was more. As Black Elk told Neihardt: “I saw that the sacred hoop of my people was one of the many hoops that made one circle” (26). Sweeney explains the results of this vision, “Black Elk came away called to heal more than just his own people; the sacred hoop was a symbol that stood for all people everywhere. This same broader understanding of the sacred–and his own calling–would allow him, later, to see another religious tradition and how it might make sense of himself and his place in the world” (26).

Also formative in Black Elk’s childhood was hearing much talk among his people of the threat of White Europeans coming from the east and pushing Native tribes further west as they came seeking gold, natural resources to plunder, buffalos to shoot, and land to clear for their homesteads and farms. Driven in part by the economic depressions of 1837 and 1869, the White people came west practicing a self-reliance that had a vicious underbelly of disregarding and debasing Native American land and rights. Black Elk confronted this threat up close when at age 10 he fought in the Battle of Little Bighorn in which his second cousin, Crazy Horse, led the Lakota to kill Lt. Colonel George Custer and defeat his Seventh Cavalry.

Not long after the Battle of Little Bighorn, Buffalo Bill Cody created his Wild West Show with alternate versions of Custer’s death. Black Elk joined the show, traveled across the U. S. and played for weeks at Madison Square Garden before going on to England and France. While in England the troupe performed twice for Queen Victoria, the second time at Windsor Castle. The show ran six months in London with an average daily attendance, according to one source, of thirty thousand and then went on to France.

This episode of Black Elk’s life raises the question of why he would knowingly participate in such blatant exploitation of his own people. Sweeney thinks that he saw the Wild West Show as a way to fulfill the vision seen by his grandfathers for his future–to bring wholeness and healing to his people. In other words, he believed that joining the Big Show and traveling to Europe would help him learn about the White people of European descent who were such a threat to his people. Sweeney quotes Black Elk as saying, “Maybe if I could see the great world of the Wasichu, I could understand how to bring the sacred hoop together and make the tree bloom again at the center of it.” Then Sweeney comments that in Lakota the word for Whites wasichu, literally means “a greedy person who takes the fat.” (36)

Some years after Black Elk’s return to the Pine Ridge Reservation and to life as a medicine man, he married Katherine War Bonnet, a Catholic convert, and the couple had three sons. After her death in 1903, he also converted to Christianity, and on St. Nicholas day in 1904, the thirty-eight year-old Lakota holy man took the baptismal name Nicholas. Missionary work on the Pine Ridge Reservation had been going on for decades, an activity related to the colonialism of Native American lands and a part of the complexity of Black Elk’s story. The Catholic Jesuit missionaries under whom he was baptized had a theological understanding that was different from most other missionaries. They recognized that the Lakota religion and attitude toward the Divine was not antithetical to Christianity. In Nick they saw a person who had the gifts to become a catechist, a teacher of the faith. His memorization and communication skills were remarkable, and he himself saw a seamless transition from his vocation as a Lakota holy man to a Catholic catechist.

Sweeney presents Nicholas Black Elk as a powerful Christian witness who was credited with bringing more than 400 people into the church in his decades of work as a catechist and missionary. He became so highly regarded and led such an exemplary life that in 2016 his grandson led a group who presented a petition for his canonization and that case has now proceeded to Rome.

In his introduction, Sweeney writes that Black Elk

“. . . bridged Western and Native religious life in a way that is sure to make people on both sides somewhat uncomfortable. So, just as Native people may feel that the integrity and sanctity of their spirituality and practices are being threatened, Christians can feel the same when faced with someone who, in himself, incorporates Indigenous spiritual traditions into a historic faith that they thought they knew”(x).

For those who are baffled by the life and work of Nicholas Black Elk, Sweeney quotes a line from Nostra Aetate, one of the documents of Vatican II: “The Catholic Church rejects nothing that is true and holy in [non-Christian] religions.” And he adds that though the statement is shocking to many of the faithful, “it would have made good sense to Black Elk” (83). In our time of huge religious and cultural division, Sweeney’s book gently but powerfully offers a way forward.

Originally published in Englewood Review of Books and used by permission

Thank you so much for this. I had grown weary of the romanticism surrounding Native religious figures with accompanying disdain for Catholicism in the same people. Here, as I already intuitively felt, the two co-existed in a powerful way.

LikeLike